7. Crusade, Pilgrimage and Defence of the Gospel in the High Middle Ages

| Key Dates # |

|

|---|

| 1118 | The Knights Templar are founded to protect Jerusalem and European pilgrims on their journey to the city

|

| 1140 | Birth of Peter Waldo, founder of a Protestant church known as the Waldensians (declared heretical in 1184)

|

| 1147-1148 | Second Crusade, influenced by Bernard of Clairvaux; further division with Eastern Christianity

|

| 1179 | Third Lateran Council

|

| 1181 | Birth of Francis of Assisi

|

| 1187 | Muslim armies under Saladin re-capture Jerusalem

|

| 1189-1192 | Third Crusade

|

| 1200-1204 | Fourth Crusade; Constantinople sacked

|

| 1209 | Inquisition ("crusade") against Waldensians proclaimed

|

| 1209 | Founding of the Franciscan Order by Francis of Assisi

|

| 1212 | Children's Crusade - most end up dead or sold into slavery

|

| 1215 | Fourth Lateran Council. Waldensians condemned. Dealt with transubstantiation,

papal primacy and conduct of clergy. Decreed that Jews and Muslims wear

identification marks to distinguish them from Christians.

|

| 1216 | Dominican order approved by the Pope; their charter was to oppose heresy

|

| 1219-1221 | Fifth Crusade; Francis of Assist meets the Sultan

|

| 1224 | Birth of Thomas Aquinas

|

Overview

The period known as the High Middle Ages (11th-13th centuries) were marked by major changes in

Christendom, especially in Western Europe. Political control was increasingly consolidated in

the hands of the kings. Technology developed rapidly. The seeds of centuries of mistrust by the

Muslim world were planted. Ongoing efforts were made to regain control of the Holy Land. The

organised church actively promoted the crusades and promises of eternal rewards, forgiveness

and help by the saints were common. Hundreds of thousands of men, women and children went

on crusades - large numbers perished. The first official arm of the Inquisition was established.

The Crusades (continued)

The Second Crusade (1147-49)

In 1144 Muslim armies captured Edessa, one of the principal Christian outposts in the East. The

entire population was slaughtered, or sold into slavery. The fall of Edessa aroused Western

Europe to the danger posed to the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and led to another crusade.

The leader of the Second Crusade was the abbot of Clairvaux, St Bernard. Great enthusiasm

accompanied his preaching (like Peter the Hermit during the First Crusade); he roused "warriors

of the Cross" from every level of society (barons, knights, and common people) to the defence

of the birthplace of Christ. Kings and emperors (including France's Louis VII and Germany's

Conrad III) were also impacted by the movement.

Of the great number of crusaders who set out from Europe, only a few thousand escaped

annihilation in Asia Minor at the hands of the Turks. Louis and Conrad, with the remnants of

their armies, made a joint attack on Damascus, but raised the siege after a few days. The

crusade accomplished nothing.

In the interval between the Second and the Third Crusade, the two religious military orders,

known as the Hospitallers and the Templars, (1129; so named because their headquarters were

located on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem) were formed. During the Third Crusade, still another

order, known as the Teutonic Knights was established. The objects of all the orders were

protecting pilgrims, caring for sick and wounded crusaders, guarding the holy places, and

battling for the Cross. These three orders were joined by other knights, and increased in wealth

through the gifts of pious supporters.

Over time, powerful and jealous enemies) sought to destroy them. Falsely accused of

blasphemy and blamed for Crusader failures in the Holy Land, the Templar order was destroyed

by King Philip IV of France in 1312.

Insignia and Execution of the Templars

The Third Crusade (1189-1192)

Having made himself Sultan of Egypt, Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub (or Saladin, born in 1138 in

Tikrit, Iraq, died in 1193, buried in Damascus) united Moslems of Syria and advanced against the

Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Crusaders engaged him in battle near the Lake of Galilee,

resulting in a rout of the army and the capture of their king. The Christian cities of Syria opened

their gates to Saladin and Jerusalem surrendered after a short siege.

News of the fall of Jerusalem spread consternation throughout western Christendom. Demands

for another crusade were strong. Once more thousands (including King Philip Augustus of

France, King Richard I, "the Lionheart", of England, and the German emperor, Frederick

Barbarossa) set out for the Holy Land. Emperor Frederick was drowned while crossing a swollen

stream, and the most of the survivors of his army, disheartened by the loss of their leader,

returned to Germany. The English and French mustered beneath the walls of Acre, which the

Christians were then besieging. After one of the longest and most costly sieges, the crusaders

forced the inhabitants to capitulate. When Saladin refused demands for payment of a ransom

for Muslim prisoners (including an offer to exchange them for the True Cross of Christ) over 3000

men, women and children, were beaten to death, axed or killed with swords and lances.

King Richard remained in the Holy Land from 1191-1192. His campaigns gained for him the title

of "Lion-hearted", but he could not capture Jerusalem. Tradition declares that when, during a

truce, some crusaders went up to Jerusalem, Richard refused to accompany them, saying that he

would not enter as a pilgrim the city which he could not rescue as a conqueror.

King Richard and Saladin finally concluded a truce. Christians were permitted to visit Jerusalem

without paying tribute, had access to the holy places and remained in control of the coast from

Jaffa to Tyre. King Richard then set sail for England, and with his departure from the Holy Land

the Third Crusade came to an end. Subsequent crusades did not significantly change the

disposition of either side. After 1291 Jerusalem would remain under Muslim (Ottoman) rule until

it fell under a British Mandate on 11 December 1917.

The Fourth Crusade and the Fall of Constantinople to "Christian" Forces (1202-1204)

This crusade was aimed at re-taking Muslim-controlled Jerusalem, through Egypt. Instead the

Christian (Eastern Orthodox) city of Constantinople was sacked in 1204. The campaign was

interpreted as the last straw in the Great Schism between the Eastern Orthodox Church and

Roman Catholic Church. Constantinople, thus weakened, was vulnerable to ongoing attacks from

Crusaders and Muslims alike, leading to its final collapse to Turkish Muslim forces in 1453.

The Children's Crusade was a popular movement in Europe during the summer of 1212.

Thousands of young people took Crusading vows and set out to recover Jerusalem. Lasting only

from May to September, the Children's Crusade lacked official sanction and ended in failure;

none of the participants reached the Holy Land. The 2005 movie, "The Kingdom of Heaven"

(Produced by Ridley Scott), portrays the struggle between the Crusaders and Muslim armies over

control of Palestine, in particular Jerusalem.

Muslims continue to hold deep resentment against the crusades. Many Jews in Europe also

perished at the hands of crusaders en route to the Holy Land, who identified them as non-

Christians and (therefore) the "enemy". Some historians lament the loss of life, disruption to

European society and costs of the crusades; others see them as instrumental in breaking down

feudalism and bringing about essential social and agrarian reform.

Saladin

The Fall of Constantinople

Some Influential Christians During This Period

Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard was born in 1090. He was the founding abbot of Clairvaux Abbey in Burgundy. He

entered the Benedictine Abbey of Citeaux in 1112, bringing thirty of his relatives with him,

including five brothers. In 1115 he was sent to Clairvaux, the Valley of Light, to set up a new

monastery after the Cistercian (ie from Cireaux) model. He imposed austere system in

monasteries in which he was involved; he claimed this was so that he could protect the faith

from heretics.

As a young abbot Bernard published a series of sermons on the Annunciation. These marked him

as a gifted spiritual writer. His works and personal style attracted many to Clairvaux and other

Cistercian monasteries.

Bernard was drawn into a controversy between his own monastic movement and the established

Cluniac order, also a branch of the Benedictines. This led to one of his most controversial and

most popular works, his Apologia. Increasingly popular, he was sought out as an advisor and

mediator by the rulers of his age. He was involved in bringing healing following a papal schism

that arose in 1130 with the election of the "antipope" Anacletus II. He preached the Second

Crusade and sent armies on the road toward Jerusalem. In his last years he went to the

Rhineland to defend Jews living there against persecution.

Bernard and Dominic

Bernard was sceptical of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of Mary. He held some

doctrines that the Reformers would later emphasise, eg righteousness through faith. He held to

a mix of the Reform doctrines and those of the Roman Catholic Church of his day.

Bernard wrote several key works about grace and free will, the mystery of the Gospel, humility

and love. His conception of justification was subsequently important to Calvin and Luther.

- "The reason for loving God is God Himself. The measure of that love lies in loving Him

beyond measure." (On the Love of God)

Bernard had a protracted and bitter public debate with Peter Abelard.

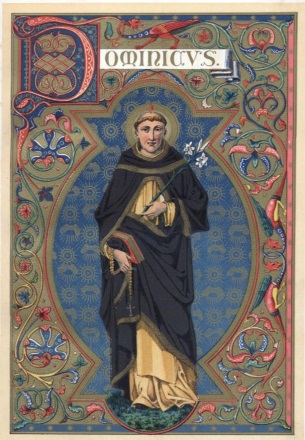

The Dominicans

The Dominican Order (or "Order of Preachers") was a "mendicant" (begging) movement founded

by a Spanish priest named Dominic (1170-1221) in the early 13th century. Dominic identified the

need for greater education and engagement with society on the part of the church. He became

famous for his theological disputations against "heretics", particularly the Albigensians in

Southern France. (The Albigensians, more commonly known as the Cathars, were a gnostic sect

that held that matter is evil and only spirit is good; this was a challenge to the doctrine of the

Incarnation). During this time the Inquisition was established (targeting a range of movements,

including the Albigensians and Waldensians, from 1209), for which the popes appointed mostly

Dominicans as Inquisitors due to their theological training. Dominicans became known as the

"Domini canes", lit "dogs of the Lord", a play on words that reflected resentment their role in

inquisition.

The Carthusians

The Carthusian Order (established 1084), also called the Order of Saint Bruno after its founder, is

a Roman Catholic monastic order that was originally established to encourage retreat and

contemplation, away from the common life, for Christians who desired to commit their lives and

time to God alone. The order includes both monks and (since 1145) nuns. They are a

community of hermits; members do not eat or work together. The order has its own Rule, called

the Statutes. Traditionally, Carthusians do not engage in work of a pastoral or missionary

nature. As far as possible, the monks have no contact with the outside world. They believe that

their contribution to the world is their life of prayer, which they undertake on behalf of the

Church and the human race. Their lives are highly regimented.

Today, there are Carthusian monasteries in Argentina, Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal,

Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, the UK and the USA, however the overall number of

monks and nuns is very small.

Mediaeval Friars

Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage was encouraged by the church in the Middle Ages because it was believed that if

anyone prayed in shrines or to the relics of "saints", their sins would have a better chance of

being forgiven and they would go to heaven. Other people also believed that they would be

cured from their illnesses and receive miracles that they needed.

Serious-minded pilgrims engaged in constant devotions while en route, and some carried prayer

books or portable altars to assist them. Monasteries located along the pilgrimage roads provided

food and lodging and also offered masses and prayers. Some monastic churches also housed

relics of their own. During the Middle Ages, pilgrims often travelled in order to win indulgences,

that is, the Church's promise to intercede with God for the remission of the temporal

punishment for sins confessed and forgiven. Some pilgrims believed that if their effort involved

pain or suffering that would improve their chances of gaining God's blessing or forgiveness.

Wealthy people sometimes preferred to pay others to go on a pilgrimage for them.

Jerusalem

Helena, the mother of Constantine, made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 327. She caused

churches to be built on the reputed sites of the Nativity and of the Ascension. She was also

credited with finding the "true cross" of Christ during the building of Constantine's church at

Golgotha. Access to Christian pilgrimage sites was one of the reasons for the Crusades (entry to

Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Antioch and other sites important to Christians was made difficult by

Arab Muslim occupants, then barred by the Seljuk Turks.

Rome

The city of Rome became another major destination for pilgrims. Easier to access (for European

pilgrims) than the Holy Land, Rome had also been the home of many martyrs, including the

Apostle Paul; the church taught that the Apostle Peter was buried in Rome as well. The places

where they were buried attracted pious travellers from a very early date. Constantine erected

great basilicas over the tombs of Peter and Paul, and pilgrims visited these as well as other

churches associated with miraculous events. What distinguished these sites was the presence of

holy relics, material objects like the bones or clothes of saints, the sight or touch of which was

supposed to draw the faithful nearer to saintliness.

Rome was particularly rich in relics, but as the Middle Ages progressed, other places acquired

important relics and became centres of pilgrimage themselves (with all the economic benefits

this brought).

Santiago de Compostela

From the eleventh century, large numbers of pilgrims flocked to Santiago de Compostela in

northern Spain, where the relics of the apostle Saint James the Greater were believed to have

been discovered around 830. Santiago de Compostela became the third most visited pilgrimage

site in Christendom. It was also a major focal point for attempts to take back Spain from Muslim

rule, in a campaign known as the "Reconquista", or "Reconquest".

I walked several hundred kilometres of this walk in 2005. Many mediaeval traditions, including

the ability of travellers to stay at "refugios" in old churches or monasteries (for a small fee)

continues. Some pilgrims believe that if they die en route to Santiago their sins will be forgiven

and they will go to Heaven; there are graves at several points along the route. The Camino de

Santiago was the central theme of a 2010 movie, "The Way", produced by Martin Sheen and his

son Emilio Estevez.

Canterbury

The Cathedral in Canterbury was a popular destination for English pilgrims, who travelled to

witness the miracle-working relics of Thomas Becket, the Archbishop who was martyred in his

church at the hands of knights of King Henry II in 1170 and canonized shortly thereafter. When

Becket was killed local people obtained pieces of cloth soaked in his blood. Rumours soon

spread that, when touched by this cloth, people were cured of blindness, epilepsy and leprosy.

It was not long before the monks at Canterbury Cathedral were selling bottles of "Becket's

blood" to pilgrims. Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (14th Century) is a collection of

stories told by participants on pilgrimage from Southwark to the shrine of Thomas Becket.

The death of Thomas Becket

Routes of the Camino de Santiago

Others

Another important shrine in England was at Walsingham, where there was a sealed glass jar that

was said to contain the milk of the Virgin Mary. Erasmus visited Walsingham and described the

shrine as being surrounded "on all sides with gems, gold and silver." He reported that water from

the Walsingham spring was "efficacious in curing pains of the head and stomach."

At other shrines people went to see the teeth, bones, shoes, combs etc. that were said to have

once belonged to important Christian saints. The most common relics were nails and pieces of

wood that the keepers of the shrine claimed came from the cross used to crucify Jesus.

Relics were the centrepieces at other sites, including St. Winifred's Well, Lindisfarne,

Glastonbury, Bromholm and Saint Albans; when people arrived at the shrines they would pay

money to be allowed to look at the relics; in some cases pilgrims were permitted to touch and

kiss them. The keeper of the shrine would give the pilgrim a metal badge that had been

stamped with the symbol of the shrine. These badges were then fixed to the pilgrim's hat so

that people would know they had visited the shrine.

In Palestine, it was possible to visit a cave that was supposed to contain the beds of Adam and

Eve and a pillar of salt that had once been Lot's wife.

I visited the Church of Carolus Borromeus in Antwerp, where the relic of Justus, a Roman boy

whose family converted to Christianity, is said to cure headaches and nerve pain.

Discussion: should Christians today go on pilgrimages (many do)? What value are they?

The Reconquista

The Reconquista began in 718 when King Pelayo of the Visigoths defeated the Muslim army in

Alcama at the Battle of Covadonga. This was the first significant victory of the Christians over

the Moors. Over the next several hundred years Christians and the Moors were involved in

ongoing conflict, punctuated by long periods where little occurred. The Moorish advance into

France was stopped by the armies of Charlemagne, but recovering the Iberian Peninsula would

take over 700 years. During the latter part of the Reconquista it was considered a holy war

similar to the Crusades. The Catholic Church wanted the Muslims removed from continental

Europe. Several military orders of the church such as the Order of Santiago and the Knights

Templar fought in the Reconquista. The campaign did not end until the fall of Granada in 1492.

The Waldensians

The Waldensian movement was started by Peter Waldo, whose goal was to return to a purer

Christianity and bringing others to the Gospels, outside of the organised church. This was an

important step because at the time the Gospels were only available in Latin or Greek and church

structures made it difficult for outsiders who did not wish to become full-time priests and so on

to go forward. Waldo had made his living as a merchant. He underwent a spiritual crisis during

which he began to feel that his life was not keeping with the teachings of Christ. He had

become wealthy and worried that this had come at the expense of his spiritual well-being.

Inspired by stories of earlier Christians Waldo decided in 1173 that he wanted to become a

wandering preacher and give away all his possessions. He hired two priests to translate parts of

the New Testament into French so that he could study them.

The archbishop of Lyons forbad Waldo preaching without the approval of the church. Waldo

allowed his wife to retain their possessions and left his family to live an "apostolic life."

Waldensian preachers travelled two-by-two (following the example of the apostles - Mark 6:7-

13). Calling themselves "the Poor in Spirit," Waldo and his followers became known as "the

Poor of Lyon.

Waldo attended the third Lateran Council (1179) in Rome and was confirmed in his vow of

poverty by Pope Alexander III. In due course, however, he was excommunicated and the

movement was banned by Pope Lucius III (1184, during the Synod of Verona). He then found

sanctuary among like-minded believers in the Waldensian Valleys of Italy, who accepted him as

their leader.

The Waldensians rejected most of the sacraments (except baptism and the Lord's Supper) and

the notion of purgatory. Their views were based on a simplified approach to the Bible, living by

high moral standards, and criticism of abuses in the organised church. Attracting others who

were disillusioned by organised Christianity the movement spread rapidly to Spain, northern

France, Flanders, Germany, southern Italy, Poland and Hungary. The church responded with

persecution and execution. Though the Waldenses confessed regularly, celebrated communion

once a year, fasted, and preached poverty, they repudiated such practices as prayers for the

dead and the veneration of saints, and they refused to recognize secular courts because they did

not believe in taking oaths.

By the end of the thirteenth century persecution had virtually eliminated the Waldensians in

some areas, and for safety the survivors abandoned their distinctive dress. By the end of the

15th century they were confined mostly to the French and Italian valleys of the Cottian Alps.

Remnants of the Waldensian movement continue to exist in a number of countries around the

world, including the USA.

Waldenses Confession of 1120

- We believe and firmly maintain all that is contained in the twelve articles of the symbol,

commonly called the Apostles' Creed, and we regard as heretical whatever is inconsistent with

the said twelve articles.

- We believe that there is one God - the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

- We acknowledge for sacred canonical scriptures the books of the Holy Bible. (Here follows the

title of each, exactly conformable to our received canon, but which it is deemed, on that

account, quite unnecessary to particularize.)

- The books above-mentioned teach us: That there is one GOD, almighty, unbounded in wisdom,

and infinite in goodness, and who, in His goodness, has made all things. For He created Adam

after His own image and likeness. But through the enmity of the Devil, and his own

disobedience, Adam fell, sin entered into the world, and we became transgressors in and by

Adam.

- That Christ had been promised to the fathers who received the law, to the end that, knowing

their sin by the law, and their unrighteousness and insufficiency, they might desire the coming of

Christ to make satisfaction for their sins, and to accomplish the law by Himself.

- That at the time appointed of the Father, Christ was born - a time when iniquity everywhere

abounded, to make it manifest that it was not for the sake of any good in ourselves, for all were

sinners, but that He, who is true, might display His grace and mercy towards us.

- That Christ is our life, and truth, and peace, and righteousness - our shepherd and advocate,

our sacrifice and priest, who died for the salvation of all who should believe, and rose again for

their justification.

- And we also firmly believe, that there is no other mediator, or advocate with God the Father,

but Jesus Christ. And as to the Virgin Mary, she was holy, humble, and full of grace; and this we

also believe concerning all other saints, namely, that they are waiting in heaven for the

resurrection of their bodies at the day of judgment.

- We also believe, that, after this life, there are but two places - one for those that are saved,

the other for the damned, which [two] we call paradise and hell, wholly denying that imaginary

purgatory of Antichrist, invented in opposition to the truth.

- Moreover, we have ever regarded all the inventions of men [in the affairs of religion] as an

unspeakable abomination before God; such as the festival days and vigils of saints, and what is

called holy-water, the abstaining from flesh on certain days, and such like things, but above all,

the masses.

- We hold in abhorrence all human inventions, as proceeding from Antichrist, which produce

distress and are prejudicial to the liberty of the mind.

- We consider the Sacraments as signs of holy things, or as the visible emblems of invisible

blessings. We regard it as proper and even necessary that believers use these symbols or visible

forms when it can be done. Notwithstanding which, we maintain that believers may be saved

without these signs, when they have neither place nor opportunity of observing them.

- We acknowledge no sacraments [as of divine appointment] but baptism and the Lord's

Supper.

- We honour the secular powers, with subjection, obedience, promptitude, and payment.